Whistling wind rattled heavy branches, there was a drizzle

of leaves and a single fruit thudded onto the red earth. Footsteps in the

distance grew rapidly, then a red-robed figure burst through the bushes, the

smell of powder on his matchlock was still fresh. “Oye! OYE! Come here. You,

come! Now!”

A squire darted up the hill, his body glistened with mud and

sweat, “yeah” he panted. Half squatting, he scratched his calf with his beating

stick.

“The emperor is missing.”

“Huh?” the boy looked up at his uncle

“The emperor is fucking missing!” the uncle hissed back at

his boy.

“Hari have mercy!”

“Shh! Shh…” He grabbed his nephew by the shoulder.

“What are we going to do?” The boy’s voice cracked.

“Listen we-“

“If the Turks find out” His uncle shushed him again; then he

whispered. “If the Turks find out, they’ll skin us.”

Suddenly there was a boom and crackle in the distance.

They darted in the direction it came, “That’s him!” they

said, then darted back at each other with skin-saved grins. Together, uncle and

nephew ran down the little mud hill to where the other boys were.

“Alright. Boys.” Uncle grasped for breath for a moment.

“Spread out as far as you can. Choose one to link up with the other parties on

either side.”

“That’s a big circle, sardar!”

He nodded and spat like a man.

“What are we hunting?”

“The emperor… and we’re not hunting him” he apologized.

The momentary power made nephew bark at his playmates, he

was barking orders, ironically, at hunting attendants. One moment they were

here, the next they had scurried into the dark. For some reason (probably

habit) they still beat at the grass with their sticks; even though they were

hunting the emperor. But they were not hunting him, so they clasped their

sticks in apology. A second shot of the emperor’s matchlock rang off.

They found him in a clearing, the now setting sun gracefully

showed his face. The circle closed in gradually, and gradually they saw the scene

more clearly. In the centre of the light stood a dazzling Turk in saffron robes,

in one hand he held the golden stirrup of a brilliant Arabian horse, in the

other against the ground was a golden smoking matchlock; the Emperor’s.

But he was not the emperor.

The emperor was amidst chattering bodyguards and attendants;

some of their nobles were there too. He was slumped against a rock the same

colour as his tunic, his hand resting on a matchlock which it held

simultaneously, pointing to the sky. His legs were not tucked under him but they

were crossed in front, as if to catch his leaning torso. It was not a grotesque

image, however. In fact it reminded many Hindu attendants of the

meditating yogis.

“The emperor complained of thirst.” The saffron Turk boomed

as the curious circle closed in. “We prepared him a seat. Then he became

unresponsive. We fear he is unwell.”

“He isn’t unwell.” Nephew stepped out, “He’s entered Samadhi sir.”

“Seh-moh-dee?” The Turk grimaced.

Uncle scurried into the emperor’s shadow and studied his

face. He turned to the Turk, “A high state. His mind has gone to oneness.” The

Turk turned around and raised his brow; Uncle realised he was too close to his study.

He stepped back towards the Turk, “Mirza,

I believe you Muslims call it Wujud.”

“Oh?”

Then the emperor opened his eyes and raised his head, so

sudden and alert it was as if he had been listening to the conversation, not

that he had been.

“Take off your shoes, for the land upon which you stand is

holy.”

The penetrating words sounded familiar, but uncle did as the emperor

asked without giving it much thought.

The emperor rose and the little murmuring that was left died

out completely. In the shadow of a rock the colour of his tunic he proclaimed

“May all the animals in any of our hunting circles be released, in the name of

God.” And with that his eyes became brilliant.

But there was the heaviness of rude shock in the air. Had the

emperor become nauseated? How could one of the lineage of Genghis and Timur

dishonour himself in such a way? Stretched stories of this episode would reach

his enemies for certain.

With a mix of concern and curiosity the attendants ran off

in all directions, beating the grass as they went. Emperor Akbar took seat once

more, and a blue-robed one poured and passed him a cup of Ganga water; his

favourite. “Keshav Das, Manohar” he summoned. In an instant Uncle and Manohar

were in front of him. Uncle knew what the emperor would ask, and the regret of

studying his face melted away into lightness.

“May this instance be painted, for it is dear to my heart

and memory. Manohar will paint everything”

Uncle swallowed. Hari be merciful.

“but my face, may Keshav Das paint my face.” Hari was kind.

“May these images be submitted to Shaik Abul Fazl. May he

include them in the grand chronicle of our reign.” At the mention of his name,

a bejewelled Arab-looking courtier sprang up and began to scribble on some

parchment he miraculously produced.

Now Manohar stepped forth, his eyes darted around the

setting studiously for a moment, “Emperor, would you have this painted in the Hindu

style? The palate would suit the colours here. Or perhaps the European style?

I’ve been studying the Bible you gifted me.” (Uncle Keshav remembered where he had

heard the emperor’s penetrating words from earlier.)

“In the Timurid style, we would prefer. This episode has

softened our heart, so may you use softer colours.” Then he leaned closer to

the two painters and spoke softly, “I trust your visions, Mano and Kesu. Do

with it what you like. But I do want soft Timurid colours… you are dismissed.”

The painters gave of their salutation and stepped backwards.

When they were at a respectable distance, they turned around and walked back to

their own parties. Behind them the emperor conversed passionately with an

audibly concerned Abul Fazl.

Keshav Das approached his nephew, his mind still re-tracing

lines of the scene, eye contact broke his vision; “Do you remember where our

horses are?”

“Yee-No. But they will be easy to find.”

Uncle rapped his nephew lightly at the back of his head with

a “Tsk tsk.” and continued walking. The attendants assigned to him watched him

patiently.

“Alright boys, back to the city” he shepherded, right then

they broke their patient stillness and raced behind him.

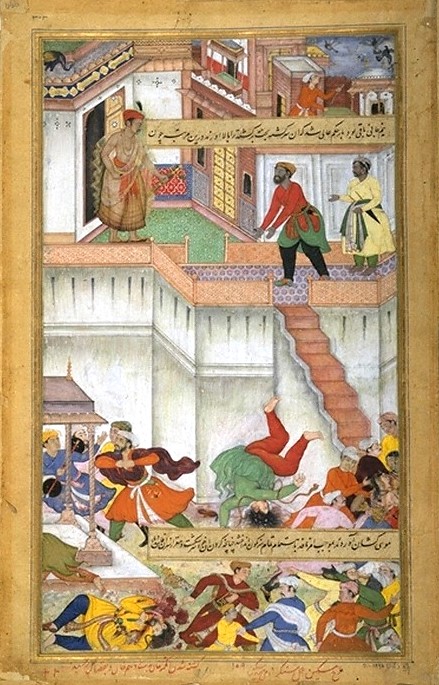

Akbar's hunting attendants find him in a trance

Akbar paced up and down moonlight lit marble in his courtyard.

His mind was greatly weighed down by thoughts, sometimes they made him

sometimes chuckle to himself and sometimes wince with regret. Very soon now

birds would start singing amidst the fruit bearing trees, and the sun would

make the rose-scented fountain and its channels glow brilliantly. Another

sleepless night for Akbar.

Footsteps grew in the distance.

He tore himself from his thoughts and considered calling out,

but realised that it was only a single pair of feet which raced in his

direction. A dazzling eunuch was at the door in an instant, bowing the usual

courtesy; she held a torch to her face and Akbar saw that it was Zaida; he

smiled at her.

“May the emperor be at peace. Mirza, the queen-mother has arrived.”

The thought jolted him awake, “Mother? Already? Make sure

she is well rested. I will see her after holding court tomorrow.”

“Emperor she, pardon me, she wishes to see you immediately.”

He stroked his chin, “Well. Fine. May there be solitude here

then.” The emperor of Hindustan, grandson of Babur, felt a deep child-like

anxiety. It was the fourth watch of the night, after all.

Zaida bowed courteously again and stepped backward into the

darkness, “I will arrange a perimeter of sentries.”

Hamida Banu, mother of Akbar, journeying via boat to visit her son

Akbar waited in the now agonizing silence, but it was only

for a few moments. Far sooner than he expected, the shape of the queen mother

was at the courtyard doorway. He, of course, knew her as Hamida Banu; his maman. Then he wondered why he was

anxious in the first place.

Her soft face stepped into the light, and then she glided

into the courtyard, arms outstretched, like a blue robed phantom.

“Oh my Jalal-uddin, Oh my Akbar” She planted two kisses on

his cheek, in the manner of the Persians; and indeed her voice was in their

manner too. “Is it true? Has he gone mad?” She paused her motherly caressing to

look at his eased face; “but you don’t look mad.” she said, sounding almost a

little disappointed.

Akbar broke into a smile “I see you have become a little too

invested in harem gossip, maman.”

“Harem gossip? Manner-less child! Haven’t you heard? After

you’re little incident in the hunting ground all the eastern provinces are up

in arms!”

He remembered why he was anxious again.

“They’re saying you’re not fit to rule; that it would be

better for you to renounce everything and become a dervish.” She continued.

“I do like the sound of that.”

“Jalal-uddin!” She slapped the emperor of Hindustan on his

shoulder. Then she stroked the hair under his turban. He suddenly saw himself

as a boy in the desert, on the run from his father’s enemies. She stroked his

hair so then too.

“Do not forget the lineage you come from. You are not a

Qadari, or a Chisti. You are a Gurkhan. You are a Mughal. A warrior. Not a

mendicant.”

Akbar was silent.

“Send a delegation of your clerics over to them, son. Let

them vouch for your honour.”

He huffed, “The clerics don’t even speak in court anymore.

Not since I abolished the Hindu taxes. Now they just stare at me. In protest.”

“You need them behind you.”

Akbar gathered in his chest his voice of authority, “I need

the love of my people. I am the Shah of India. Of all Indians.” It came out sounding meek instead.

The sapphire ring on his finger glinted in his eyes; on it

was the insignia of his ancestor Timur. “The Sufis say the Hindus and Muslims

worship the same god maman. If he

chose me to rule his people, how can I just call myself a Muslim? The Sufis say

god is neither Hindu nor Muslim. How can I, as his appointed shadow, call

myself one or the other then?”

He turned, letting out a frustrated sigh, and allowed the moon

to distract him. She waited for a minute.

“Jalal-uddin” she then stepped towards him, “Your father was

a Sunni, and I a Shia. It did not matter to me when I married him. I knew times

were changing, this is natural when countries talk... You know, I only wanted a

husband whose collar my hand could touch, not one with a skirt I could not

reach," She chuckled at her own favourite pet phrase, "your father and I, we understood our god to be one.”

Akbar’s eyes became brilliant, “so you understand then?”

“But we broke the laws of our faiths and disgraced the ways

of our forefathers, some would say.” Her tone was cold now, “and we did it for

the greater good Akbar, because your father had a duty as a king. We brought

the Persians and Turks together. Had we not, your father would not have been

able to reclaim his throne for you. Sometimes we must sacrifice our beliefs for

stability.”

Akbar’s brilliant eyes shattered, “You really want me to

send the clerics then?”

“Try and find another way, if you can.” He found both a

challenge and comfort in her words, so he found a rug and took a seat on it.

“Oh Jalal-uddin…” she unravelled his turban and consoled his

grey head, “It’s not easy to be king. You are as sleepless as ever. But how

soundly you used to sleep, my boy.”

Thoughts overfilled his mind and spilled over as words,

“maman, Khan Baba does not let me

sleep.”

“Khan Baba? Bairam Khan has been dead for years, child.”

“Yes. I killed him.”

“You sent him to Mecca, Jalal-uddin...”

“I sent him to his death. My heart was light when I did.”

Akbar became a desert child again, only this time he was

being seated on a hastily made earthen throne. Bairam Khan, a white faced

Persian was declaring that Jalal-udin Mohammad Akbar was the legitimate ruler

of India. Akbar; the holy warrior. Akbar; slayer of the infidel. Akbar was

destined to defeat the Hindu Hemu, wicked usurper of Delhi and Agra. God was

surely on their side, for an arrow would find Hemu’s eye, and it bring him

tumbling down before the desert child and his white guardian.

“Kill him” Bairam Khan had said.

But the child only touched his prisoners chin with his

sword and said, “There, Khan Baba.”

“Emperor! This is not the way of Genghis.” Still, the child

threw his sword onto the ground. Bairam Khan knelt before him, but then picked

up the sword and with a clean sweep lopped Hemu’s head off to roll. Then, as if

to remind Akbar of his ancestors, Bairam Khan ordered all the prisoners be

dealt with in the same manner, and for pyramids of their skulls to be erect

outside the gates of Delhi and Agra. “May it be so. In the name of the emperor,

in the name of God!” he had said, but Akbar could not remember being asked.

And he would say nothing.

A boy Akbar hawking with a nobleman, probably Bairam Khan

Bairam Khan had been with Akbar even when they wandered endlessly

from his father’s enemies. There were few who were there then, and Akbar prized

them above all.

And one of them was his Anga,

his milk mother. Her name was Maham Anga, and on many nights she too kept him

from sleep.

The people of the steppe honoured their milk mothers,

revered them even. So it was for Akbar, who was of the brood of Genghis and

Timur. Maham Anga had fed Akbar from her right teat, and her own Adham from her

left. When mother and father were exiled in Persia, then baby Akbar was a

hostage of his treacherous uncle. In those days, Maham Anga would nurse them with a dagger in her hand, knowing Akbar’s life could be ended in a whim. She

sang steppe songs through the night, arising deeply from her throat. It kept her

two sons sleeping, and it kept her awake.

Akbar and Adham knew each other from then. Their feet

climbed and grasped each other as she fed them. Some years later, their tangled

feet would kick up red earth as they wrestled. Akbar would be on the verge of victory,

then Adham would strike him. Akbar would lash out at him with another blow, but

they would end up laughing and throwing dirt at one another. They would suffer

Maham’s slaps and sermons together too.

Some nights she would hold them still with stories of their

steppe forefathers. “When Genghis Khan was still named Temujin, he waged war

with his blood brother Jamukha. When he conquered him, he spared him an ignoble

death. The Mongols did not spill noble blood. So Jamukha’s back was broken

instead.”

As the boys grew older, the distance between their hearts

grew too. Akbar feared hearing Adham beat his attendant with a horse whip. He

did not like the way Adham would interrupt the dancing. He dreaded the way

Adham would handle the dancing girls. While Akbar found peace in the taming of

mad elephants, Adham lay recluse with opium and double distilled arak. Akbar would dress as a Hindu, stealing out of

the palace he would strike up talk with bored shopkeepers. But Adham turned to

numbness with stern faced Afghan mercenaries. Like with Bairam Khan, Akbar

stayed silent through it all. Maham Anga would change that.

“But Khan Baba was my father’s most loyal general” Akbar

would say to her, his voice cracking.

“Your father is dead! Bairam Khan tells you he is regent.

But he acts like a king Jalal-uddin! That should be you, my son!” She peered

into his eyes, “Are you not a man? Doesn’t every man get his inheritance?”

And Akbar began to feel like a man. He was eighteen years

old now, and already he was influencing the mustache fashion of court. Every

man in Delhi, even Adham, dressed like him, they were all sporting his trademark Rajput whiskers. Only Bairam Khan still

kept his beard. But Akbar was ready to play king.

When court was held, Akbar spoke before Bairam Khan could

speak for him. Then he thanked Bairam for his years of service to his father

and himself, and prescribed for him to be with god at Mecca. When Bairam Khan

laughed, Akbar boomed “May you travel to Mecca to be with God.”

Maham Anga’s hand was on Akbar’s shoulder. Bairam stopped

laughing.

The court remembered silently that when the late Emperor

Humayun captured his traitor brother, Bairam had advised sending him to Mecca, he

died on his way there. But Bairam knew he would not die, and he knew he would

not bow before this boy. His boots thundered defiantly as he stormed out, as

did his voice.

“Emperor Humayun’s honour is tarnished. Some witch has

poisoned the Emperor’s ears against me. I will return from Mecca. I will make

things right.”

Many

months later, Akbar received a message from his Khan Baba. It was a couplet which

read;

“He who blows at a

lamp lit by God

Sets fire to his

own beard”

Bairam

Khan was dead, stabbed in the desert by an Afghan who owed him vengeance.

Akbar

was finally free to rule with Maham Anga’s blessing. Her hand was on his

shoulder when he proclaimed before the court, “May Adham Khan replace Bairam Khan as commander-in-chief.” His heart ceased

being light.

Maham

Anga sent Adham Khan south, to conquer Malwa. Many days past, and Akbar’s spies

returned. They had seen savagery.

“Emperor,

Adham was stumbling on opium and arak, he began celebrating victory in the

streets. He humiliated the Hindus and forced many of them to convert. The

Islamic leaders had protested; saying “The Quran says there is no compulsion in

religion.” So Adham Khan had replied with slaughter. None were saved from his

rage, my lord. Now the bards only sing the of the tragedy of King Baz-Bahadur

and lady Roopmati…”

Akbar

left before they could finish.

“Patience

Akbar, Patience!” Maham Anga had advised him, but he knew now how to break

his silence. That very night he alighted his horse and blazed down south. A

while later, close to Saranghpur, he saw glittering in the distance. Then a

trooper glistening in silk burst into his vision.

“Majesty! Adham Khan’s camp lies

ahead.”

Adham

rode out to see his milk brother, in jubilant welcome he was making his horse

dance. Akbar did not hear his words, but saw his hand outstretched towards a

camp overburdened with glittering loot. There was a proud smile on his face, but

Akbar did not smile back. ”May Adham rub his nose in the dirt before me” Akbar

boomed.

“But Jalal-uddin…”

Akbar

was beyond listening.

Adham,

still hoping his brother would break into sudden wild laughter, did as he was

told. His nose was in the dirt now, but Akbar had yet to uncover his humour. Only

after many moments he spoke, “May the wealth be confiscated from the

dishonoured soldiers.” Then he turned in the direction he came. Akbar had seen

hatred in Adham’s glance, and it thrilled the both of them.

A humiliated Adham Khan prostrates before Akbar

“Patience

she tells me,” Akbar thought again and again on his long ride home, “Patience.”

He had lost all of that. He hated it, and he hated all of what his spies told him,

“Emperor,

Maham Anga was seen in private conference with wazir Munim Khan”

“Emperor,

Adham Khan struck the physician you sent for him.”

“Emperor,

Maham Anga was in conference with wazir

Munim Khan again last night.”

Every

day Adham grew bolder and more reckless, and every night Maham Anga spoke in

silent corners. Which other family could Akbar turn to now?

Then, he

saw the smiling face of Aziz ride up on his right, “Jalal-uddin, this entire

journey your eyebrows have been knitted. What are you thinking?”

Akbar

smiled back, “I am thinking of your family, Aziz.”

“My family?”

“Yes.

Yours. Your grandfather saved my father’s life in battle. How can such a thing

be repaid?”

“It was

repaid by allowing my family to serve his majesty,” Aziz beamed, “my

grandfather was a peasant, the emperor made his son a general. There is no debt

between us.”

Akbar’s

heart was light again, “And what a glorious service. What a brilliant general,

your father Ataga Khan! How many fields he has won, how ferocious is his

loyalty! My enemies shiver at the name of Ataga Khan. Aziz, there is a debt

between us still.”

“But

Jalal-uddin, it was his duty to-“

“And

your mother? Jiji Anga? Who nursed me

when Maham Anga could not? She made a man of me Aziz! With no vying eyes, no

promise of reward, she did. Truly, I have become Emperor by drinking her milk.”

Then Akbar reached over his horse to pat Aziz on the shoulder, “and she has

birthed a fine and loyal milk-brother for me.”

“Your

majesty-"

“Verily,

there can be no better milk-mother in all the world.”

Aziz

understood the depth of Akbar’s thoughts, patting dust away from his face he

dared not to say another word.

“I am

thinking of your family because it is my

family.” And with that Akbar rode hard ahead.

“I,

Emperor Akbar, declare before this court that Shams-uddin Muhammad Ataga Khan,

husband of my milk mother Jiji Anga, be appointed as my wazir. May he replace

wazir Munim Khan, who I release from his years of loyal service. May Ataga Khan

be bestowed with the title ‘Grand Khan’.”

“Hail wazir Ataga Khan!” The court resounded.

Then there was an uneasy silence, like the kind that follows breaking glass.

Akbar

slid into the door behind his platform-throne, and was suddenly eased to be in

his private quarters. Gliding over his marble courtyard, he pushed aside an

attendant in his way.

“But…

Emperor, Maham Anga wishes audience with you urgently.”

“Tell my

Anga I am tired from my journey from Malwa. I will visit the baths, rest, and

then be with her.”

His

eyes grew heavy, and his heart sprang lightly…

He

awoke to tumult. There was a great outrage to be heard in the audience hall

nearby. Akbar stumbled out of his apartment to see Adham Khan run up the stairs

of the courtyard, his naked sword glinting. Akbar squinted,

“Adham.

What have you done.”

“Jalal-uddin,

you ingrate! After all my mother has done for you!”

“Adham.”

“You

insult her! Shame on Timur’s blood you are, humiliate me for following his

way…”

Akbar

saw blood on Adham’s sword, “Adham! What have you done.”

“I

killed Ataga, the dog.” He hissed spitefully.

With

one pace Akbar picked up the scent of arak and opium. With another pace he

struck Adham powerfully in the temple, sending him crashing to the floor. In an

instant heavy men with swords leaped out, and with a thud threw a ring around

Akbar. The underneath of their clothes glinted. “May Adham Khan be taken atop

the walls, and thrown down from them.” The men did so. It did not kill him, so

Akbar quaked, “May Adham Khan be thrown down the walls again.”

Akbar oversees Adham Khan's execution

Then Akbar

truly dreaded Maham Anga for the first time in his life, because now she did

not have the power to scold or beat him. He was the emperor of India, and he

still dreaded her; this fear was pure.

He avoided her eyes first, then forced

himself to meet them. When she saw, the alarm in her eyes escalated. “What is

it Jalal-uddin? Akbar. Tell me.” He could not speak. “Akbar.”

“Ang-Anga.

I have killed Adham. He killed Ataga Khan. And he invaded my apartments

dishonourably” Akbar broke his forced stare, and felt sick.

Maham

Anga only looked at him for a few moments. “You have done well.” She said, and

her eyes went to the wall. Akbar briskly walked out, terror in his pace.

She died

forty days later. The sleep a murderous Adham interrupted was the last Akbar

enjoyed.

“Maman, will you

read to me?” Akbar returned to being an emperor in a courtyard, his mother’s

consoling hand on his head. “Read to you?” Hamida Banu was perplexed.

“It will help me sleep.”

“But we are two watches from dawn.”

“It’s just as well.”

Some nights, Akbar longed to become a child again. He would

wrestle with his cousins, hunt in the desert, loaf with the townsmen, and stare,

fascinated, at meditating Jaina monks. He would turn away all those who were

sent to tutor him, preferring to ride down hills or shoot arrows across rivers.

There was one tutor who he kept always, however: one whom Bairam Khan did not

send. That tutor’s name was Mir Abdul Latif, and he taught Akbar poetry.

Mir Abdul Latif, or Mir, had brilliant eyes, with lines that

reached out from their corners when he smiled. A boy Akbar would sit in his lap

and play with his silver beard while he sang the poetry of the Chisti Sufis; through

the years, Akbar stopped playing with Mir’s beard and gradually started stroking

his own, thinking pensively as Mir sang to him:

“There is colour today mother, there is colour. At my beloveds house

there is colour.

Country after country I’ve been seeking. My heart is smitten by your

colour, Nizammuddin Auliya.

Where ever I turn he is with me. There is colour today mother.”

Akbar clasped his hands and swayed with joy. The common

tongue was so musical to him, he could not help but sing along:

“I have found my guide; Nizammuddin Auliya. There is colour today

mother.

Khusrau says then came my wedding night, and I stayed awake with my

beloved

My body and my beloved’s heart became one colour”

Akbar fell in love with the poems and stories, but he could

not read. Letters would dance before his eyes and twist his tongue; this

troubled him greatly. So it was that Mir read to him every night instead:

Arabian Nights, Hamzanama, Sufi Poetry, or the Quran. Some nights he read the Baburnama, the story of Akbar’s

grandfather. When Akbar requested, Mir found him a Brahmin priest to recite the

Ramayana and Mahabharat as well. In the day Akbar made his body strong, and in

the night his mind. But his mind felt lost now. If a voice from the past read

to him again, he might dream of Mir’s song till dawn;

“O clay lamps, do listen to what I say.

Today there is colour in my master’s house, so rise through the night*”

In the courtyard, Hamida Banu had the Baburnama brought to

her. It was recently translated from Chugtai Turkic to Persian. She opened the

first page and began; “In the month of Ramadan of the year 899 and in the

twelfth year of my age, I became ruler in the country of Fergana”

…and Akbar slept.

Akbar as a child

*Amir Khusrau's Rung (translation ours)

.jpg)